In 2012, members wrote stories of Edmonton section adventures and people to celebrate our first hundred years. Here is one of those stories, in which Zac Robinson describes the life of Margaret Gold Brine, whose generosity benefited Edmonton and whose mountain climbing accomplishments were famous in the 1920’s.

Margaret Brine (1898-1985) is a name that many Edmontonians are no doubt familiar with – and for good reason. During her life, the selfless benefactor of the performing arts smiled upon Edmonton’s opera, its symphony, and several of its theatre groups. The extent of her financial support remained etched onto the Art Gallery of Alberta for decades (with one room named “The Margaret Brine Gallery”). The Citadel Theatre’s own Margaret Mooney cast Brine as “one of the last of the real ladies,” one with “tremendous dignity and class.” After her death, Brine left a major bequest to the Canadian Federation of University Women (Edmonton) – of which Brine was a long-time member and contributor to its academic awards – to endow educational scholarships. Today, female graduate students who demonstrate academic excellence at the University of Alberta (UofA) – Brine’s cherished alma mater – hold the Margaret Brine Graduate Scholarship for Women with distinction and pride.

And so it’s hardly surprising that civic stalwarts and pillars of the Edmonton arts community remember Brine in the highest regard. What many people don’t realize is that – before 1928, when she married Charles A. Brine (1888-1963), an Edmonton house builder whose financial success enabled her philanthropy – Miss Margaret Gold, as she was then called, was equally renowned for another “high” calling: mountain climbing. In fact, during the mid-1920s, her accomplishments in the alpine made front-page headlines in newspapers clear across western Canada.

Climbers today likely strain to recognize the name. You certainly wouldn’t know it from popular histories of mountaineering in Canada, even from the few important texts dedicated to the accomplishments of women. Here, Brine, if anything, registers as the faintest blip. If there’s a chief reason for the oversight, perhaps it’s this: eighty-nine years ago, Brine skipped her chance to become the first woman to climb Mount Robson, letting two others make the ascent. Instead, she purportedly “partied” at the ACC’s 1924 summer camp and climbed the highest mountain in the Rockies the next day. Two months later, she topped off the remarkable season by climbing the Matterhorn.

Conrad Kain and Margaret Gold at the 1924 ACC Mount Robson Camp. Courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (V105-PA-7746).

Brine was born in the last years of the nineteenth century – the daughter of a Presbyterian minister – in Fort Langley, British Columbia. As a young student of classics at the UofA, she developed a passion for mountains, one that equaled her love for drama and the performing arts. The Edmonton Section of the ACC became a sort of surrogate family. By 1920, her tenacity and “fun-loving style” earned her a place beside Edmonton’s best: climbers like the section’s Chair, Harry Ernest Bulyea (1873-1976), the first Dean and founder of the Faculty of Dentistry at the UofA, and “the Skipper,” Cyril Geoffrey Wates (1884-1946), author of the club’s then-popular “Songs for Canadian Climbers” and, later, the club’s President (1938-41). Together, from the ACC’s 1920 Mount Assiniboine Camp, the three demonstrated their civic and section pride with the first recorded ascent of an unnamed peak that lay on the southern side of the Simpson River Valley. Brine documented their success in her field diary: “built our big cairn, fixed Kodak with string and stone arrangement, snapped ourselves, left record of our climb and name ‘Mount Edmonton’ in cairn and prepared to look for an easy way home.”

First Ascent of “Mount Edmonton,” 1920. Left to right: Cyril Wates, Margaret Gold, and Harry Bulyea. Courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (V105-PA-7746).

Days later, just before leaving the area, Brine was tapped by E.O. Wheeler (1890-1962) – the camp’s manager, who, a year later, would participate on the 1921 British Reconnaissance of Mount Everest – to join a rope on the “keynote” peak of the camp, Mount Assiniboine. It was a huge honour. Despite the club’s early acceptance of women among its membership (contrary to British model, which didn’t permit female members until the 1970s), there existed a clear distinction between what was considered an appropriate climb for a lady and for a gentleman. Throughout its first decades, the club relegated its female members to the easier routes at its camps, whereas the more prominent men were typically awarded opportunities to attempt the more difficult peaks for the prestige of the club. Brine noted her exchange with Wheeler in her diary: “In the evening, Major Wheeler asked me if I should like to go on Assiniboine rope on Thursday? Would I? Held myself in and as evenly and normally as possible asked if it might be sooner. After some consultation Tuesday was fixed upon. Was someone happy? Could scarcely sleep.” Brine’s was, perhaps, the second ascent of the mountain by a woman.

Throughout the early 1920s, Brine’s education continued – both in academics and mountaineering. She travelled to Paris to study art and literature at the Sorbonne, climbed Mont Blanc in the Alps, and completed a Master’s Degree from the UofA. After the famous 1924 Mount Robson Camp – where she rubbed shoulders with the likes of Phyllis Munday (1894-1990) and guide Conrad Kain (1883-1934) – she assumed a teaching appointment at her alma mater, a post she held until 1928, as well as a position on the executive committee of the Edmonton Section of the ACC.

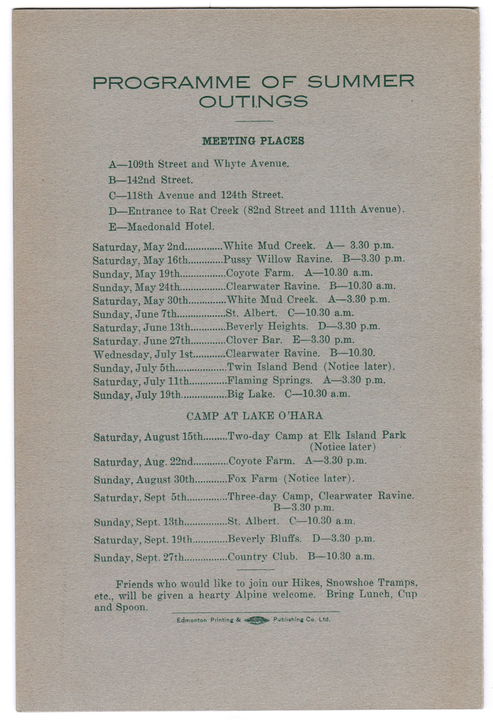

What Brine accomplished in the 1920s was extraordinary – and not just for reasons related to gender. The activities of the Edmonton Section were hardly what they are today. The dirt road from Edmonton to Jasper, which followed much of the abandoned Grand Trunk railway bed, didn’t open until 1928; the completion of the Banff-Jasper Highway was another decade away. And it wasn’t until well after the Second World War that the Jasper-Edmonton highway was paved. Opportunities to climb in the mountains during the 1920s were thus scarce for most section members. They required a trip on the train, usually followed by extensive backcountry travel with few amenities. For this reason, a typical summer program during this decade boasted section trips not to the Rockies, but to local Edmonton haunts, like the Whitemud Creek, for example, which today separates neighbourhoods in Riverbend and Terwillegar from other neighbourhoods on the south side of the North Saskatchewan River.

Program of Summer Outings. Edmonton Section of the ACC. Summer, 1925. Nancy Brine Collection.

Near the end of the decade, Edmonton was even the site of its own “alpine” hut: “the Eyrie,” it was called, built near Quesnel Heights on the banks of the river. And so Brine’s track record in the mountains – Assiniboine, Mount Blanc, Robson, the Matterhorn; some of the most sought after peaks in the world – is all the more impressive and deserving of commemoration.

After 1928, Brine’s climbing activities gradually ceased, although she remained a member of the Edmonton Section for her entire life. And like so many Edmonton institutions, the ACC, too, later benefited from her philanthropy. In 1971, Brine generously donated sufficient funds to build an adjoining cabin to the ACC’s Clubhouse on their then-new Canmore property. Equipped with a full kitchen, two washrooms, and a spacious living room with a fireplace, the private, self-contained facility offered a spectacular view of the Bow Valley. ACC members from Edmonton, Calgary, and Banff all volunteered long hours of planning and hard work to complete the cabin for its opening in 1978. Brine requested that the cabin be named in memory of Dr. Fred Bell (1883-1971), who served as the Club President from 1926 to 1928. Her request is hardly surprising. From 1950 to 1964, Bell served the ACC as its Honorary Librarian and shouldered the immense task of reorganizing and cataloguing the club’s now-famous library, one of the largest collections of mountaineering books on the continent. In 1978, Bell’s wife, Marcella, addressed an assembled crowd at the cabin’s official opening and expressed her “deep personal gratitude to Mrs. Brine and the Alpine Club of Canada.”

As the Edmonton Section celebrates its 100th anniversary and we look back to commemorate all of the great events and individuals that have shaped our section, we’d do well to shine a light upon those selfless individuals who cared little for centre stage, cared little for public praise. It’s these individuals who are perhaps the most deserving of a little hero worship. They so often represent our best.

At the toe of the Robson Glacier. ACC Mount Robson Camp, 1924. Left to right: Annette Buck, Cyril Wates (foreground), Margaret Gold (background, standing), and unknown club member. Courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (V105-PA-7746).

Ron Chalmers, a staff writer for the Edmonton Journal, perhaps best summed it up. Chalmers was interested in Brine’s role as an Edmonton arts benefactor. And, as his 1984 interview with her concluded among her impressive art collection, he marveled at how Brine, then 86 years of age, turned away from the paintings and pointed to a bowl of fresh-cut flowers: “They really are all that matters,” she said, “beauty, and being kind to people.”