Modern day avalanche safety is a focus for the Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) and is far different from early attitudes. Read the Avalanche Safety Training and the Edmonton Section article for more information.

The winter of 1937-38 was a bad one for avalanches in the Canadian Rockies. With growing numbers of skiers enjoying the winter playground found in the mountain backcountry, it was only a matter of time before avalanches began to receive increased public attention. On New Year’s Eve, December 31, 1937, the front page of Banff’s Crag and Canyon newspaper headlined “Skiers Make Ascent of Mount Fay—Report Enjoyable Sport.” Two of the finest amateur climbers in the Rockies, Capt. Rex Gibson (1892-1957) and his young protégé Bob Hind (1911-2000), both from Edmonton, along with Douglas Crosby, of Banff, had made the successful ski ascent of Mount Fay from the Elizabeth Parker Hut.

Tragically, the very same day the headline was printed, Gibson and Hind, this time in the company of the twenty-year-old John Bulyea (1917-1937), son of the prominent Edmonton Section member Dr. Harry Bulyea (1873-1976), were caught in a large avalanche while skiing on the slopes of Mt. Schaffer. The Crag and Canyon reported the incident in its next issue:

On Friday, Gibson, Hind and Bulyea were skiing on a slope below Mount Schaffer. They were zig-zagging up the slope, when suddenly they heard a crack above them and realized an avalanche was descending. At this time, Gibson was the higher up of the three to the right of center. Bulyea was in the center a bit lower down the mountain, with Hind over to the left of the avalanche track. Warnings were shouted, Gibson making it to the right, Hind to the left, but Bulyea being in the center caught the full force of the big avalanche. Gibson got clear but Hind was caught in the outer edge and, as he had been seen by Gibson, the latter immediately went to his rescue and within a few minutes had extricated him from the slide. The two men then set desperately to work searching and probing for their companion, but after three hours gave up the search and started for Field to raise the alarm.

The slide’s runout, according to the Banff newspaper, was 120-metres wide. The deposited debris – a jumble of snow, shale, earth, and boulders – was estimated to be ten metres deep. Bulyea was fully buried, undetectable in the days before sophisticated avalanche transceivers. His body was not discovered until the spring.

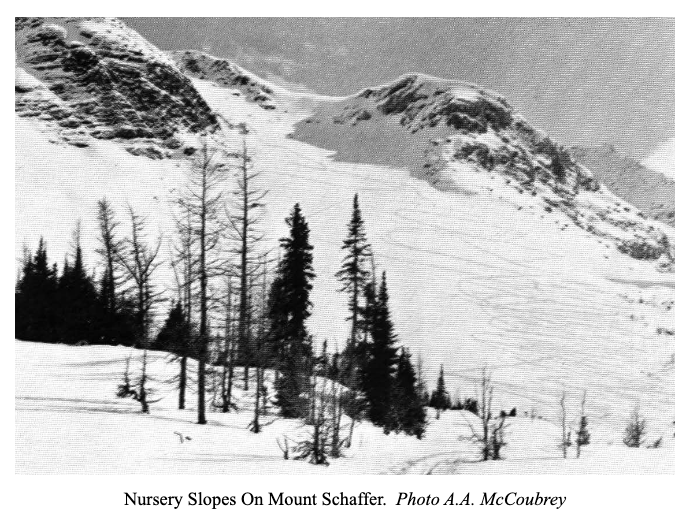

The avalanche accident received widespread attention in the Canadian press, including front-page coverage from the Edmonton Journal, the Edmonton Bulletin, the Calgary Daily Herald, and the Winnipeg Free Press. It was even reported in the Montreal Gazette. The articles varied little from press to press. For the most part, they described the events that led up to the incident, as well as the ensuing search efforts, based from various accounts from park officials and those individuals involved. Mild weather was the alleged culprit, and no blame was attributed to the skiers. But some reports hinted that the Alpine Club of Canada (ACC) was partially responsible. The Crag and Canyon, for instance, reminded readers that “in the 1936 issue of the Alpine Journal [Canadian Alpine Journal], a picture of the slope on which the avalanche which caught Bulyea is shown. In the published picture, the slope is criss-crossed with ski trails and is described as being a ‘nursery slope.’” Thus pointedly the report came to an end.

The impact of the criticism is difficult to measure: no official statement addressing the incident was ever issued by the ACC. To be fair, the CAJ article referenced by the newspaper did warn that the slopes of Mt. Schaffer were, in years of normal snowfall, “subject to avalanche early in the season.”

Nevertheless, distancing the ACC from any accountability, the club’s reaction was clearly one of careful avoidance. For example, there is not one single reference to the accident in the pages of the 1937 CAJ (published in 1938), while, conversely, Gibson and Hind’s winter ascent of Mt. Fay received ample coverage. An obituary for Bulyea did not appear in the journal, and the proposed 1938 ACC ski camp, to be held only months later, was cancelled without explanation. Moreover, the entire ski-mountaineering section of the CAJ, contrary to the editor’s earlier prediction, disappeared from the issues following the 1937 volume.

Unquestionably, the Mount Schaffer incident was a tragedy for the Edmonton Section. And it was also a setback for backcountry skiing and the ACC. But public criticism soon faded. Mountain skiing in the backcountry was here to stay. By the spring of 1939, the whole event seemed forgotten. Club organizers held a ski camp at the ACC’s Memorial Cabin (an early precursor to the Wates-Gibson Hut) in the Tonquin Valley, near Jasper, and plans to build a cabin for winter activities in the Little Yoho Valley were renewed. Construction on the “Stanley Mitchell Hut,” as they called it, was completed in autumn, and it welcomed its first guests the following spring.

Searching through avalanche debris for John Bulyea on the so-called “nursery slopes” of Mount Schaffer. Photograph, Bob Hind, January 1938. Courtesy of Pete Hind.